The Fourth Discourseman

It’s something of a truism to observe that today belief in God is less ubiquitous than it was in past incarnations of our society. I could cite Pew Centre research that seems to show the decline of religion in the United States, or similar data for European countries; but the main point is that atheism has ceased to be a radical, beyond-the-pale belief system, and is instead one of a growing plurality of acceptable creeds one can comfortably subscribe to. That, at least, is one essential part of secular modernity, to which so many western countries adhere. Leaving aside my own belief (following C.S. Lewis, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and more recently, Jordan Peterson) that no one is really an atheist – that we all worship some transcendent Other, however atheistically we might attempt to construe that – this nonetheless represents a significant shift in the fabric of society and our collective moral universe.

And it’s not hard to see that Christians find this development somewhat difficult to negotiate. It seems to be one reason, for instance, for the shift from what we might (perhaps polemically) call Christ-centred evangelism, typified by Billy Graham’s rallies, or John Stott’s 1952 Cambridge mission, the addresses of which later found their way into book-form as Basic Christianity, to the apologetics model, exemplified by the ‘Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics’ and the trend amongst university Christian Unions to run ‘Big Question’ events where various ‘difficult’ aspects of Christian truth claims are carefully defended (another example of this would be Rebecca McLaughlin’s book Confronting Christianity). The phrase that often gets bandied around in defence of such a move – which in my less charitable moments I am tempted to see as a Christian affirmation of the ‘God in the docks’ scepticism of western modernity (spoilers: one day we’ll be in the docks) – is ‘people are coming from further back’. Later in life, that was even John Stott’s view, though I doubt he would have been fully approbatory of the apologetics-heavy model of today – Basic Christianity, he admitted, would in the early twenty-first century have to function more as a primer for new Christians than a means of introducing non-Christians to the central dogmas of the faith.

So we are in something of a tizzy about the threat of atheism and unbelief. There are doubtless many avenues we could wander down for answers to this predicament. But I want to suggest here that there are lessons our past can teach us for such an undertaking. That might come as something of a surprise, if the above remarks are true, and we do indeed live in an age novel for the fact that atheism has at long last emerged from its centuries-long Christian proscription and climbed to the status of a respectable creed. How can the early modern era – one in which atheism was socially, politically and legally unacceptable – inform we who live in such uncharted territory, in a world so alien to it?

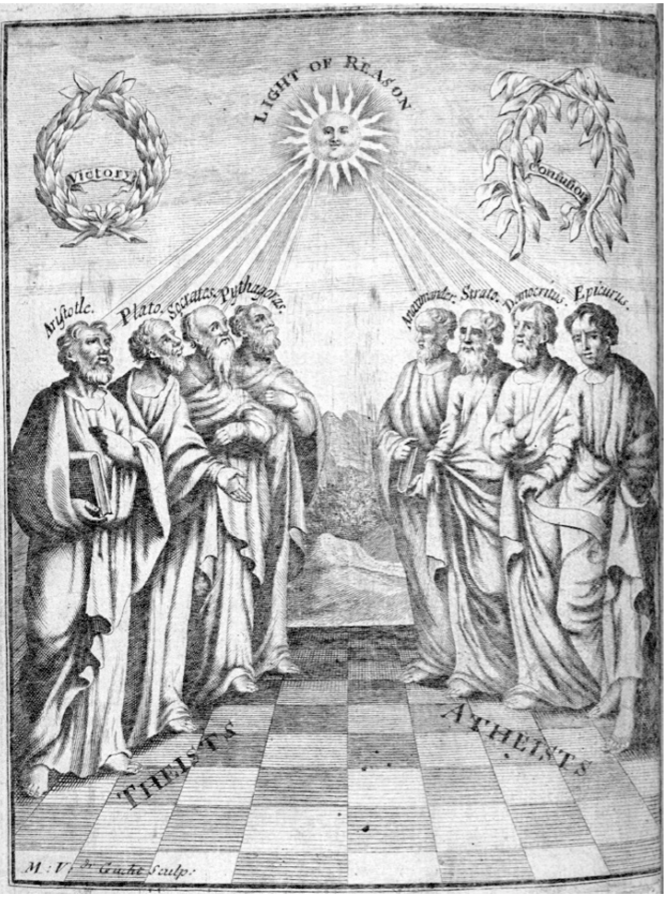

The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were not times of widespread atheism – or indeed, much atheism at all. There were myriad religious and theological works published in this period, but not a single work advocating what would be recognised as atheism today (though there was a revival of Epicurean ideas in the seventeenth century, which to its critics amounted to a kind of atheism). But despite this, atheism seems to have been a very real concern for many. Particularly in England, figures from across the confessional and political spectrum produced laboured refutations of atheism, and proofs of God’s existence. The irony of these works is their combining strenuous efforts to disprove the atheist with the claim both that atheism was utterly foolish and that few, if anyone, actually subscribed to it (the puritan divine Stephen Charnock believed that in the entire history of the world there had been, at most, twenty actual atheists). If the former was true, then why the need to marshal such intellectual energy against it? And if the latter, why the need to print so many books to that end?

There may well be many reasons for this somewhat baffling phenomenon. But one that certainly seems salient to me is the structure of the moral universe of Christendom. These were Christian societies. Our laws were (and are) derived from Christian dogmas; the national church provided the bedrock of social and moral order, with the parish (and its church) the most basic building block of the state; the monarch was (and again, still is) both the governor of the Church and anointed by God (not simply instituted by elected representatives, as in modern Spain). The divine was close at hand, providing social order, direction, and the mutual trust that is so essential for communal flourishing and economic exchange. That’s why the apparently liberalising philosopher John Locke, often seen as a harbinger of modern liberalism and toleration, excluded atheists from those whom the state could and should tolerate. Civil society simply couldn’t function if atheistic beliefs were permissible, for who else could be the guarantor of contracts, oaths and obligations, save God, our future judge?

But the problem with the moral order of Christendom is that spiritual dogmas and what we might call civil dogmas obtain to wholly different kinds of certainty. It is in the nature of spiritual truth (and I use the term uncomfortably, for reasons I hope future blog posts will elucidate), which concerns the transcendent and the divine, to fall short of epistemic certainty. It was the desire to know as God knows, after all, that was at the heart of the first sin; and the taking of the fruit was in that sense unsuccessful, if the book of Ecclesiastes, or simply universal human experience through the ages, are anything to go by. How can we be fully certain about that which, by its very nature, escapes our grasp? That certainty is of an eschatological tenor, a future hope (1 Cor. 13:12); for the time being, we live in the tension between the eternity that by design lies in each of our hearts, and our relative incapacity to fathom it (Ecclesiastes 3:11). There is clearly something of a paradox here, for the same St Paul who saw the truths of Christ in a glass darkly was also certain enough of the truths of Christ to forsake all else for them. Perhaps it is better to think not in terms of a ubiquitous notion of ‘certainty’ that merely differs by degrees with respect to varying truth claims, but rather of different kinds of certainty that are incommensurate. Certainty as to the truths of Christian dogma results from faith that is divine, suited to its object. But it certainly is not epistemic certainty of the kind claimed by modern science. It leaves space to wrestle with God; it must be content with mystery. In short, it is the certainty of doxology.

The everyday ‘dogmas’ of civil society – the basic principles of justice, for instance; knowing that X happens when Y is done – simply cannot exist on that same level of transcendence. We might derive them from divine truths, the highest truths – indeed, I believe it is absolutely necessary that we do. But frayed edges, mystery, and transcendence, are less tolerable in the realm of lived relations (personal, societal) and quotidian existence than they are when pertaining to the divine.

The problem with Christendom, though, was the gradual intertwining of these two planes. The transcendent became wrapped up in the everyday, something we particularly see in late-medieval Christianity in the west, where the boundaries between the dogmas of faith and the ritualisms of local identities and practices became distinctly blurred. When this happens, the realm of everyday exigencies doesn’t give up its need for robust certainty – that would make society unable to function. Instead, the spiritual surrenders to the drive for epistemic certainty, so as to be brought into line with the everyday with which it has now become almost commensurate.

That, at least, seems to me to be one reason for the shoring up of theistic belief against the spectre of early modern atheism. The teachings of the church had become so enmeshed with the fabric of civil existence – especially with the stratospheric rise of an elaborate vision of canon law in the high Middle Ages – that they had slipped into a different epistemological realm, that of epistemic certainty. Faced with unbelief – whether of the so-called ‘practical’ kind, or the (apparently rarer) existential kind – the assertion of certainty (look how foolish atheism clearly is!) was by necessity regurgitated. To give it up would be to shake the foundations of civil society and its moral framework.

I have little by way of ‘lessons’ from this first observation. To me, it raises more questions than answers. It seems to point to that eternal tension between the realm of the spirit in Christian thought and its inevitable institutional and societal expression. At this point I find that a rather intractable issue to negotiate, or disentangle; and history bears out the difficulty our forbears likewise faced in this regard.

But there is a more obvious lesson that at least goes some way towards justifying the title that heads this page. And that is that our early modern friends epitomise, in their reaction to the threat of unbelief they believed they faced, a perennial human impulse, but one that I believe to be especially damaging, if not especially prevalent, within the Christian Church. When scepticism is not an option – and outright scepticism (and here I am using the old sense of the word, as the position that nothing truly can be known) never is – then epistemic certainty is leant into as a response to doubt. This was the early modern theologian’s typical position, with the exception of a few seventeenth-century Anglicans; and if book titles like The Reason for God are anything to go by, it very much remains the position of contemporary evangelicalism. We fear mystery, paradox, the limits of our own thought. To suggest that something might be more complicated than that which a fifty-page, size 12 font 10ofthose book could hope to elucidate is, one might be told, to tread that slippery (and well-trodden) slope to theological liberalism. To suggest that there might be tensions inherent in Christian thought – and I for one very much believe that to be the case – seems likewise to be an excursion down that rather amorphous path, often couched in terms of apostasy. So we batten down the hatches, shore up our dogmas, and tell the world – and ourselves – that we have all the answers.

But do we? It is a fine line between trusting in our doctrines (and with that, our ability to formulate and systematise them) and trusting in the one of whom they speak. At the heart of Christian thought cannot be the conviction that we have all the answers. Rather, it is that Christ has all the answers. He is the one in whom are hidden all the treasures of wisdom and knowledge (Col. 2:3). But they are indeed hidden in him. We see in a glass darkly, but the one who sees all and knows all is the one whom we see, and whom we trust. He is the way, the truth, and the life (John 14:6). He is not the culmination of our discovery of the truth, but its beginning, and its end. That is what made Christianity so radically different from all the impressive philosophies of the ancient world. It was not about a particular system of thought, but a person, a person who was and is the answer to it all.

We must not set ourselves up for a kind of certainty that cannot be ours this side of glory. The biggest, most profound questions of human existence cannot be zapped away by a few books from a church bookstall. We must be content, as some of the thinkers of early-modern Christendom were not, with the sheer otherness of God, and the perplexing mystery of existence. But as we do so, as we scratch our heads with Hamlet and like Qoheleth shake our fists at the heavens, we have a friend, a guide, a saviour, that none of the greatest existential philosophies can proffer. And he calls us to follow him.

One thought on “Lessons from early-modern atheism”