Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind, that by testing you may discern what is the will of God, what is good and acceptable and perfect.

I

A common line of concern amongst Christians is that our faith become a matter of the mind alone. As we conceive of it, knowledge is of two kinds. There is ‘head’ knowledge, which is important and not to be sniffed at – this is the realm of the theoretical, the abstract, the doctrinal. But then there is ‘heart’ knowledge, the real marrow of Christian growth and learning, and what truly ought to be the aim of all our studies and sermon-hearing. Without the latter we make a mockery of the former. More than that, there is a sense in which head knowledge that fails to pierce the heart is worse than ignorance, for it leaves our waywardness without excuse. So Thomas Brooks, a fiery puritan even by the standards of that most fiery era of Church history, prefaced his famous Precious remedies against Satan’s devices (1652) with the following admonition to his readers:

‘If thy light and knowledge be not turn’d into practise, the more knowing man thou art, the more miserable man thou wilt be in the day of recompence; thy light and knowledge will more torment thee, then all the Devills in hell.’

There is biblical warrant for this, of course. Knowledge puffs up, the apostle tells us (wonderfully, it “puffeth up” in the AV); and St John exhorts his readers along similar lines: “Little children, let us not love in word or talk but in deed and in truth.” (1 John 3:18) For love that exists in talk and word alone is deceitful, hypocritical; it has the outward appearance of virtue but is shorn of its true being. Such ‘love’ is of the head only, and is of a piece with the type of knowledge that St Paul dismisses as ‘vain conceit’.

There is another critique to be made of so-called ‘head knowledge’. Protestantism, a particularly wordy incarnation of an already wordy religion, has always struggled to free itself from the subjectivism that comes from so central an emphasis on the mind, on knowledge. That potential misbalance has grown particularly acute in the current attempt to de-religionise the evangelical faith. An exemplar of this movement is Tim Keller, who goes so far as to argue that Christianity so isn’t about what we do that it isn’t even a religion at all. It’s difficult not to connect this to the broader dynamics of secularisation, and the lamentable adiaphorisation of worship and religious observances that has become the norm in Christian churches across the confessional spectrum (though, it is fair to say, it is probably most explicitly found in Protestant churches). How many of us believe that God actually cares about what we do in church, the forms and structure of our worship? The rapidity with which English churches moved to conducting their ‘public’ worship on Zoom during the lockdowns of the last two years is surely indicative of how low a view Western Christians of today (myself included, it must be confessed) have of the actual actions of devotion and worship. The point of church is not doing something, but understanding something; and the latter is of course far more readily Zoom-able than the former.

Insofar as we have put into abeyance the doing of religion, we have elevated the knowing of religion. The result is, by and large, a religion of the mind. And into this milieu the typical critique of ‘head knowledge’ that stands alone is indeed welcome. If Revd. Keller is right, and we are not to be a people of religious observance per se, then at least we can be a people whose religion pierces the heart.

II

One great vice of human nature – present in my own writings, as my less charitable readers will no doubt observe – is our unfortunate tendency to be dominated by the need to react and counter the errant and erroneous. It is not enough merely to set forth the truth plainly, unbeholden to wayward ideas and practices; instead – whether for pride or ignorance, or perhaps both – we must so state our corrective case as to run into the error of overreaction. That, I fear, is what has happened in the all too necessary wariness of ‘head’ knowledge amongst many Christians today. In the well-intentioned critique of head knowledge there is an all too real danger that we miss the importance, the primacy even, of knowledge in the Christian life.

British evangelicals of a former generation were fairly avowedly anti-intellectual; the late Michael Green, for instance (himself very much a thinker), noted E.J.H. Nash’s reticence to engage with theology at any level. Despite the vigour and zeal of that generation – something I am sure we can learn from – this was a less-than-admirable trait, and something that, in God’s providence, later generations have seen fit to correct. But I wonder if rigorous thinking still remains as something of an appendage to the evangelical mind. That is, it is seen as a necessary vocation for some – either because we need academic defences of faith and doctrine, or because, for purely missiological reasons, we need believers in the field of academia – but it is not a normative feature in the life of a Christian. To my memory I have rarely, if ever, heard of Christian growth described in terms of learning, and certainly not in terms of learning doctrine. Growth is rightly understood in terms of growing in godliness, but growing in knowledge – possessing more information, having greater cognitive understanding – is rarely conceived as being a component of this.

On my understanding, that is not the biblical way. As in the verse which heads this article, one of St Paul’s chief concerns was that believers be renewed in mind. For Paul, godliness follows when the object of our mind’s activity is the ways of God. As he says earlier in the same epistle:

‘For those who live according to the flesh set their minds on the things of the flesh, but those who live according to the Spirit set their minds of the things of the Spirit.’ (Rom. 5:5)

It will be put to me that, in our post-Enlightenment thought world, we read into this text a very different concept of the mind than that which Paul had in mind. At some level that is true; Paul is not being rationalistic here. But there are ready examples of pre-Enlightenment Christian practice that seek to inculcate this mind-led piety. In the Reformed tradition, catechesis was a central part of pastoring believers; all Christians were expected to know, for instance, basic Trinitarian doctrine, Christology, the rudiments of Reformed soteriology, eucharistic doctrine, ecclesiology – the lists goes on. If an emphasis on the mind is an Enlightenment or post-Enlightenment phenomenon, then there is no explanation for why mid-seventeenth century English Christians (those of competent literacy and none) were widely expected to have a workable knowledge of such doctrinal tenets that easily surpasses that of many Christians today.

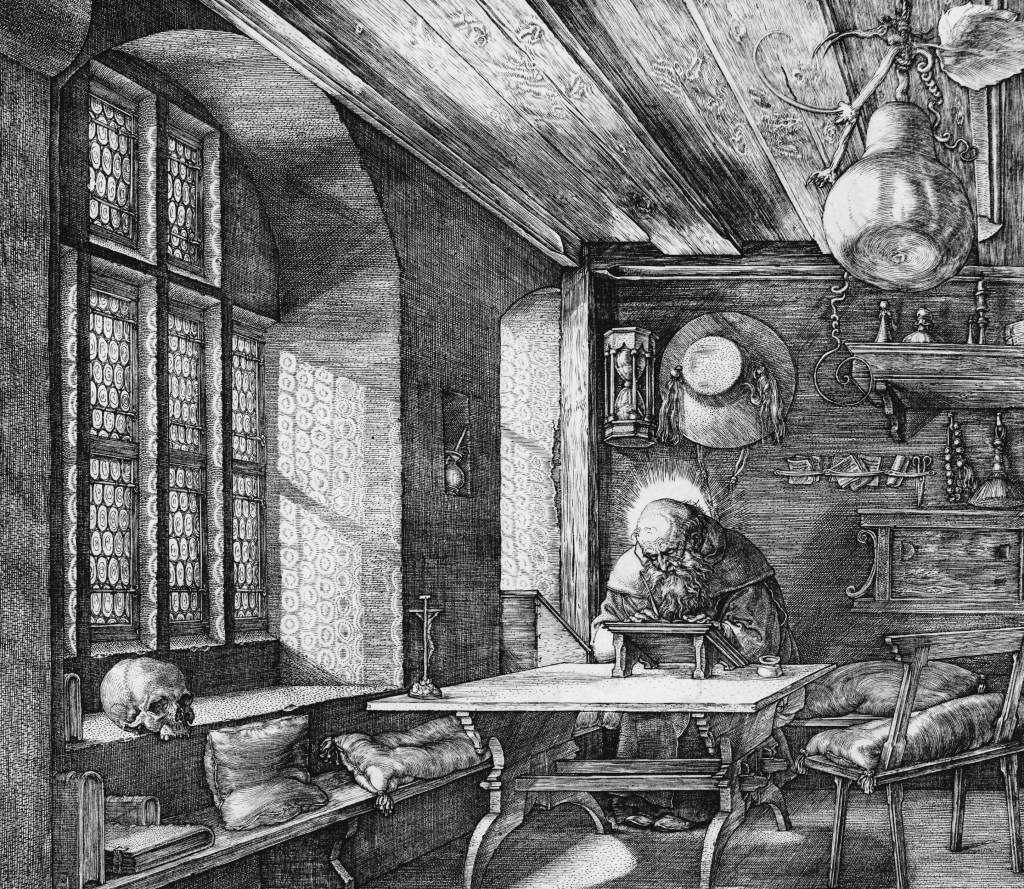

The reality is rather more embarrassing. The necessity of true intellectual knowledge in the life of a believer is not a function of the rationalistic worldview of the secular West, but a feature of Christianity throughout the ages (indeed, I would argue that aversion to emphasis on the intellect is in reality a result of contemporary Christians being far too rationalistic; but that is a point for another time). For Paul, steeped in the psychology of the Graeco-Roman world, reason must rule the passions: in Christian terms, the mind must correctly grasp spiritual matters in order for godliness and self-control to follow. That means that learning is an indispensable part of sanctification. Like Mary in Luke 10, we are called to sit at Jesus’ feet, drinking from the sweet well of his doctrine.

That means theology, and doctrine: proper, thorough, deep, difficult doctrine. It means pursuing truths that are difficult to grasp, that require the full application of intellectual and spiritual energies to mull over and comprehend. We must not be afraid of proclaiming truths that sound strange and recondite to the outsider, nor of building upon the foundation of the more basic doctrines we comprehended in the early days of our walk with God; indeed, that is our very calling (Heb. 5:11–6:2). Of course, we never leave the basic tenets of the gospel. But nor ought we to expect to learn the same things week by week, month by month. The depths of God’s revelation to mankind are there for the grasping.

That grasping is cognitive, but it is also more than that. It starts in the intellect, but it must pierce the heart and move the affections. For this reason it is a slow, laborious process. Ratiocination and meditation combine in the believer’s pursuit of true, ‘experimental’ knowledge. I shall let Thomas Brooks have the final word. After writing a 116,000 word treatment of spiritual warfare, he saw fit to pen the following warning:

‘Remember, ’tis not hasty reading, but serious meditating upon holy, and heavenly truths, that makes them prove sweet and profitable to the soule. ‘Tis not the Bees touching of the Flower that gathers Honey, but her abiding for a time upon the Flower, that drawes out the sweet. ‘Tis not he that reads most, but he that meditates most, that will prove the choicest, sweetest, wisest, and strongest Christian, &c.‘

The Fourth Discourseman

One thought on “A mind renewed”