I

I recently finished reading Patrick Deneen’s book Why Liberalism Failed. I hadn’t actually heard of it until recently, when it was pointed out to me that my claim that the big state is the close friend of individualism was already the central thesis of Deneen’s work. (Unsurprisingly, my ideas aren’t exactly original: and nor should they be.) So I popped Deneen on the mental shelf as a probably-should-read kind of a thinker. Then I happened upon a particularly insightful Paul Kingsnorth article on Unherd that sang Deneen’s praises even more profusely than had the First Discourseman to me: this book is ‘perhaps the most reliable guide to the world we live in now’. If true, that’s a good thing; we’re all in need of a few guides these days, though I’ve read enough of Kingsnorth not to expect cheery reading from contemporary commentary that receives his approbation.

Deneen’s book is indeed an extended discussion of the same ideas that I raised back in December. That’s unsurprising, given that he’s influenced by many of the same people as myself: folk like Alasdair MacIntyre, Brad Gregory, Wendell Berry, and Charles Taylor. In his case, that’s especially unexpected – as a political scientist at Notre Dame, he’s bumping shoulders in the same institution as the former two. I was surprised, actually, that he didn’t make greater reference to these thinkers, especially MacIntyre, who doesn’t make the cut at all – but then, I made no mention of the great philosopher in my own writing on similar themes.

The big idea is that liberalism is a victim of its own success. As the individual is ‘emancipated’ from the bonds of family, community, custom, culture, and place – and from the values they enclose – the state has to step in to plug the gaps left by these erstwhile mainstays of human existence. What that creates is not ‘liberty’, but its counterpart: the stifling overreach of the big state, replete with rampant over-administration and reams of red tape. One crucial point that Deneen makes – and it is well made – is that this is a feature of either side of our apparent ideological divide. The political left is comfortable with state intervention as a means to facilitate (we might say impose) ‘liberty’ upon its citizens. In America especially, this ‘liberal’ end of the spectrum positively relishes the erosion of those bonds and ties which have bound people and peoples to one another in times gone by, to be replaced only by what is a function of the autonomous will of an individual – what I have elsewhere called the attitude of ‘autonomophilia’. That is, of course, a recognisably ‘liberal’ position. But the bite of Deneen’s argument, at least for the self-professedly conservative, is that the same effect is wrought by right-wing politics and policies. An ever-expanding, globalising market as the key to prosperity; the exaltation of selfishness and greed as the mechanism of such prosperity; and the increasingly choice-driven, consumerist approach to the stewarding of resources: these are all features of the same autonomian ideology, and while they drive the liberal project they are responsible for its collateral damages, in much the same way as putatively left-wing ideologies. The confluence of the two is not more clearly seen than in corporate wokedom, where it has finally become impossible to separate the mantra of ‘you can buy anything you want’ from its sister in the liberal creed: ‘you can be anything you want’.

What ought we to replace liberalism with, then? Deneen is relatively silent on this, something for which he has received criticism. It is somewhat fitting, however, given that a central point of the argument is that liberalism provides not a new culture but an anticulture – and the only real way to see culture grow to replace it is for that to happen organically, from the bottom up. What is needed, he says by way of conclusion, is not another ideology, but new practices:

A more humane politics must avoid the temptation to replace one ideology with another. Politics and human community must percolate from the bottom up, from experience and practice. (p188)

In other words, liberalism must be replaced by culture, and culture must be cultivated – not dreamt up on the basis of faulty anthropologies and propositional theorising.

That was the problem, Deneen claims, with the tradition of liberalism that he sees running through Hobbes, Locke, and J.S. Mill (though it should be said that Hobbes, the most forceful theorist of arbitrary power, was no liberal, as Deneen recognises). Their idea, predicated upon an imaginary ‘state of nature’, was that liberty consisted, in its essence, of the absence of external compulsion – what Isaiah Berlin would later call ‘negative liberty’. Or to put the matter positively, in so far as one can, this liberty was the freedom to do whatever one wished, provided no harm was caused to another. What it destroyed, and what one assumes Deneen believes ought to replace it (however much he pleads for a forward-looking, ‘postliberal’ order), is the classical and Christian conception of liberty as achieved by virtuous self-rule, both in terms of the individual and in the polis at large.

II

There are three minor issues I have with Deneen’s work, and one major one, the elephant to which I shall return at the close. The first is a dangerous critique for any writer to make of another: which is that I am not so fond of Deneen’s prose. It is too clearly, if I may be blunt, the work of a social scientist. The clauses follow on from each other with little of the rhythmic variation which might have otherwise provided respite, or simply pique the interest of the reader. Isms and ists are piled high. Take, for instance, this example, in which he is describing how liberalism undermines liberal education:

Education must be insulated from the shaping force of culture as the exercise of living within nature and a tradition, instead stripped bare of any cultural specificity in the name of a cultureless multiculturalism, an environmentalism barren of a formative encounter with nature, and a monolithic and homogenous “diversity.” (p111)

This isn’t quite the turgid and overbearing style of Berger and Luckmann; but nor is it the unassumingly musical prose of someone like Wendell Berry. That might seem like a cheap shot; and to some of my readers, it might seem hypocritical. But I am not writing a New York Times bestseller – at least not any time soon.

In the second place, Deneen’s work is too America-centric. At one level this makes sense: he is an American, working in an American university, and writing primarily for an American audience. But his failure to make this explicit runs the risk that his ideas be misapplied to societies that, while similar enough for his work to have some cogency, are different enough for some of them to be irrelevant, or worse. That the United Kingdom has let itself become a backwater of American ideas and institutions in recent decades – seen most clearly in 2020’s anti-racism protests – is one of the more lamentable features of our national conversation and political life. Deneen’s habit of almost imperceptibly flitting between America-specific analysis to that pertaining to the West more broadly makes such cross-Atlantic wash all the more likely. The salient example is his assumptions about the two wings of the politically sphere, and the understanding of ‘conservatism’ that goes with it. Though he mentions Edmund Burke in passing (p147), by and large his assumption is that ‘conservatism’ is American conservatism. But much of what passes under the conservative guise in the US is not really conservatism at all: its commitment to Jeffersonian, Enlightenment ideals of individualism could not be further from the broadly paternalistic, community-focussed and tradition-cherishing brands of conservatism found in the British isles. Though the latter has been influenced by the American right, as is clear in the case of Roger Scruton, Deneen and others like him would do well to pay more attention to the British, and indeed European, ways of doing things.

Thirdly, Why Liberalism Failed is curiously absent any real historical analysis. That would be fine, were it a work not seeking to be historical in character. And yet, that is just what it is: Deneen sets out to write the story of liberalism’s demise. But instead of evidence-based intellectual, cultural and social history, the book is full of vague claims about the way things used to be. Of course, Deneen is not trying to be a historian, and his is more a work of philosophical history, akin to that done by J.B. Schneewind or Larry Siedentop. But he would have done well to at least pay attention to those who have done the nitty-gritty of historical analysis, much like Charles Taylor does in his even more philosophical, and even more wide-ranging works of intellectual history. If Deneen’s argument is to stick, he needs to point the reader in the direction of empirical fact: both in showing that liberalism has indeed failed (something that is, more or less, assumed) and in delineating the history of that failure.

III

I come then to my elephant, my overarching gripe with an otherwise welcome work. Deneen fails to take seriously the challenge of technological development. He is aware that there is indeed a challenge here: is it not new infrastructure that has the most profound restructuring effect on human means of life and ways of interaction? Does not our technologised, hyper-connected world lend itself to the individualism and state control that Deneen decries? But his answer is simplistic: technologies flow from ideologies, not the other way round. It’s worth quoting him more fully on this:

…as we have seen, there is much concern about the ways that modern technology undermines community and tends to make us more individualistic, but in light of the deeper set of conditions that led to the creation of our technological society, we can see that “technology” simply supports the fundamental commitments of early-modern political philosophy and its founding piece of technology, our modern republican government and the constitutional order. It is less a matter of our technology “making us” than of our deeper political commitments shaping our technology. (p103)

But this is of course a false dichotomy. While I lean towards materialism in history, there is no denying the role of ideas in technological or scientific breakthrough. There must be certain ideological commitments in place for significant breakthroughs to happen: rarely is a light simply switched on in someone’s brain. Inventions require specific ideological constructs and motivations.

But those ideological commitments are deeply shaped by the physical circumstances which have given birth to them. Take, for instance, the ‘liberalism’ of John Locke, which Deneen believes to be the progenitor of the secular liberal order, and the ideological foundation that shapes modern technologies. Locke’s view of government is shaped by his view of freedom and the toleration it necessarily entails. It’s not hard to see this as arising from, amongst other factors, (1) religious conflict and strife – the Thirty Years War, and more pertinently, the English Civil Wars; and (2) a uniquely Protestant elevation of individual interpretation of Scripture and theology. The first of these put Locke, and others of his generation, on the road to theorising a religiously-neutral state; the second helped drive the necessity for that. But were these simply the result of ideological forces? The answer is a muddied ‘no’. While something of an individualising impulse might exist in the Christian creed as a kind of latent force (which Larry Siedentop has argued at length), its reification required specific physical and technological circumstances. In the case of early modern Europe, such circumstances were most famously brought about by the invention of the printing press. With knowledge more readily available, and confessional conflict played out at a more popular level, individual choice in matters of belief was augmented. And, famously, the Protestant imperative of personal study of scripture became a reality through cheaply-produced vernacular Bibles. Of course, one could claim that certain ideological conditions had to be in place for such an invention even to be thought of. That is true: Gutenberg’s ideas clearly come from the long revival of western learning that had begun with the first universities in the twelfth century. But, crucially, his invention took on a life and purpose of its own: the disseminator of knowledge became the maker of the individual, and with it a new conception of liberty.

One more example comes from the Baconianism that Deneen regularly derides. In his telling, a new approach to nature – one in which man is at enmity with the natural world, and must ransack its resources to serve his own ends – simply popped into Lord Bacon’s head with little or no precedent or invitation. But there’s no denying that circumstances made possible Bacon’s ideas, in a way that hadn’t been possible before. One was the aforementioned Protestant reformation. The historian Peter Harrison has written extensively about the relationship of Protestantism to the so-called ‘scientific revolution’. Essentially, his argument is pinned on the fact that a new, literalist hermeneutic in the reading of Scripture encouraged a new hermeneutic of nature, that other of God’s “two books” of revelation. But, as we have seen, the Protestant reformation would not have been possible without the technologies that so shaped it.

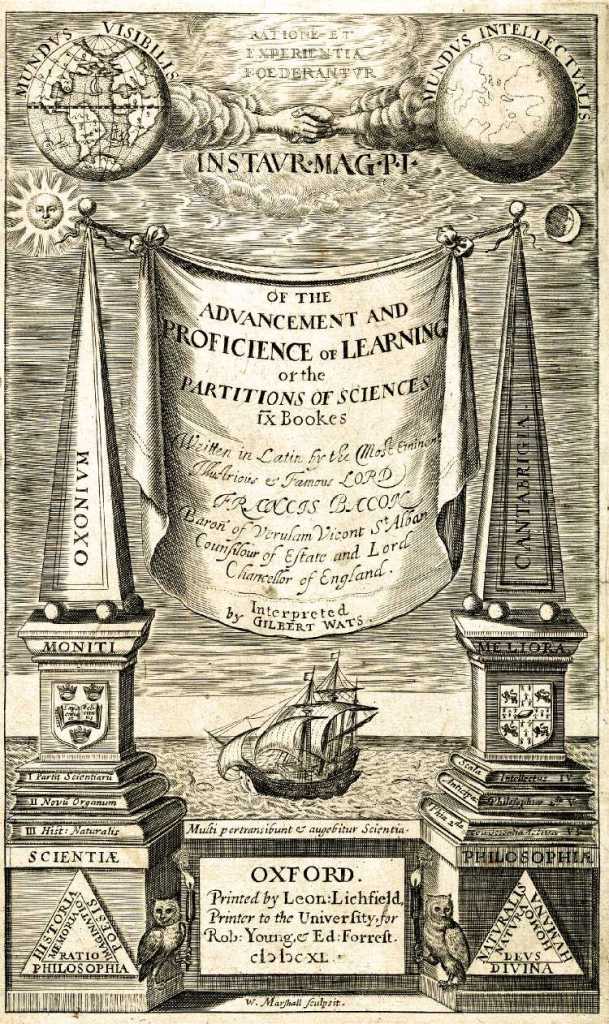

Another clear influence on Bacon was the discovery of the new world. That a whole continental landmass had existed unbeknownst to Europeans suggested that the world was not necessarily as it had always seemed: there was more to be discovered. And the ancients had clearly been wrong, in recognition of which Bacon penned his famous maxim that ‘antiquity is the youth of the world’. He himself made the influence of the discovery of the new world plain, when his Novum organon of 1620 – an intended challenge to the Aristotelian logic – depicted on its frontispiece a ship sailing into the Atlantic from Europe. That theme was revived by a later editor and translator of his Advancement of Learning, who in a 1640 edition of the work depicted a ship sailing for the new world, with one half of the globe marked as mundus visibilis and the other, unmapped half as mundus intellectualis. The visible world had been mapped, Bacon’s editor was saying: now let us map the world of knowledge yet to be discovered.

Bacon was a visionary, yes – but his work was made possible by new technologies. Ideas are always the product of material circumstances, and material ‘progress’ the product of ideas: there is no divorcing the two.

By dismissing the role of technology in shaping ideology, Deneen is able to proffer a naive view that a ‘postliberal’ order can be built. But he fails to take seriously the fact that the bird has flown the nest, and the cat is most certainly out of its bag. Our technologies have created a new system of life, and new worldviews. Importantly, as I’ve written before, even the attempt to create a different mode of life and belief is necessarily one facilitated by the structures of liberalism. For it is impossible not to act as an individual created by the liberal order – something our technologies particularly lock us into, shaped as they are by the deification of choice.

That is the elephant in the room of conservative musings about the modern order: that our technologies have far more effectively done away with the old order than we would care to admit. We are wedded to the very technologies that have wrought the world we claim to deride. And we enjoy them. Every First Things article that rails against Twitter, every pastoral idyll that might be recommended on Unherd,[1] is a monument to the paradox that is contemporary conservatism. But few are willing to see just how deeply-wrought are the changes our societies have seen in recent decades. The structures and rhythms of our lives are far more formative than our dualistic culture can bring itself to recognise, but the re-wiring of the western mind goes deep. The noumenal, the transcendent, and the sacramental have been lost in a sea of short-lived entertainments. And the age-old sources of identity and hope, spiritual and yet so earthly – the family, community, shared rhythms of life and life-tasks – have been sacrificed to privacy and the gods of human volition. These are the sources of our infrastructure, but they are also the products of that infrastructure, and their reach is greater than any conservative reaction can articulate or comprehend.

The old order is dead: let us acknowledge it. The elephant is too grand to hide. But let us not lose hope. The kingdom must still be built, indeed can still be built. And on this at least I agree with Deneen, that the change begins not with a grand new theory, nor with answering or wishing away problems that are too intractable or complex for us to overcome. It begins on the margins, the outskirts, in unexpected places. It begins with lives transformed by the gospel, in faith that a life lived in humble service of Christ has more power to transform the world than anything else this life has to offer.

The Fourth Discourseman

[1] I can’t say I read Unherd enough to know if they recommend pastoral idylls, but I hope they do.