On Sunday morning, the only email in my inbox is from Microsoft’s Viva, giving me its usual daily briefing. It doesn’t mind working on Sundays. Out the window, a different robot chirpily, absent-mindedly mows the lawn, because that’s what it’s programmed to do. It doesn’t mind working on Sundays either. The family could move out the house, the house could be demolished, the grass could grow wild for miles around, and still it would continue mowing its little patch.

In Nazi concentration camps, prisoners were not given rest. As punishment, they were made to stand up throughout the night then continue working the next day. The confiscation of rest was part of a systematic effort to dehumanise the prisoners, because rest is inherently human. Christians talk a lot about the value of work, but it’s in our rest that we most reflect God’s image as a God who completes and is satisfied.

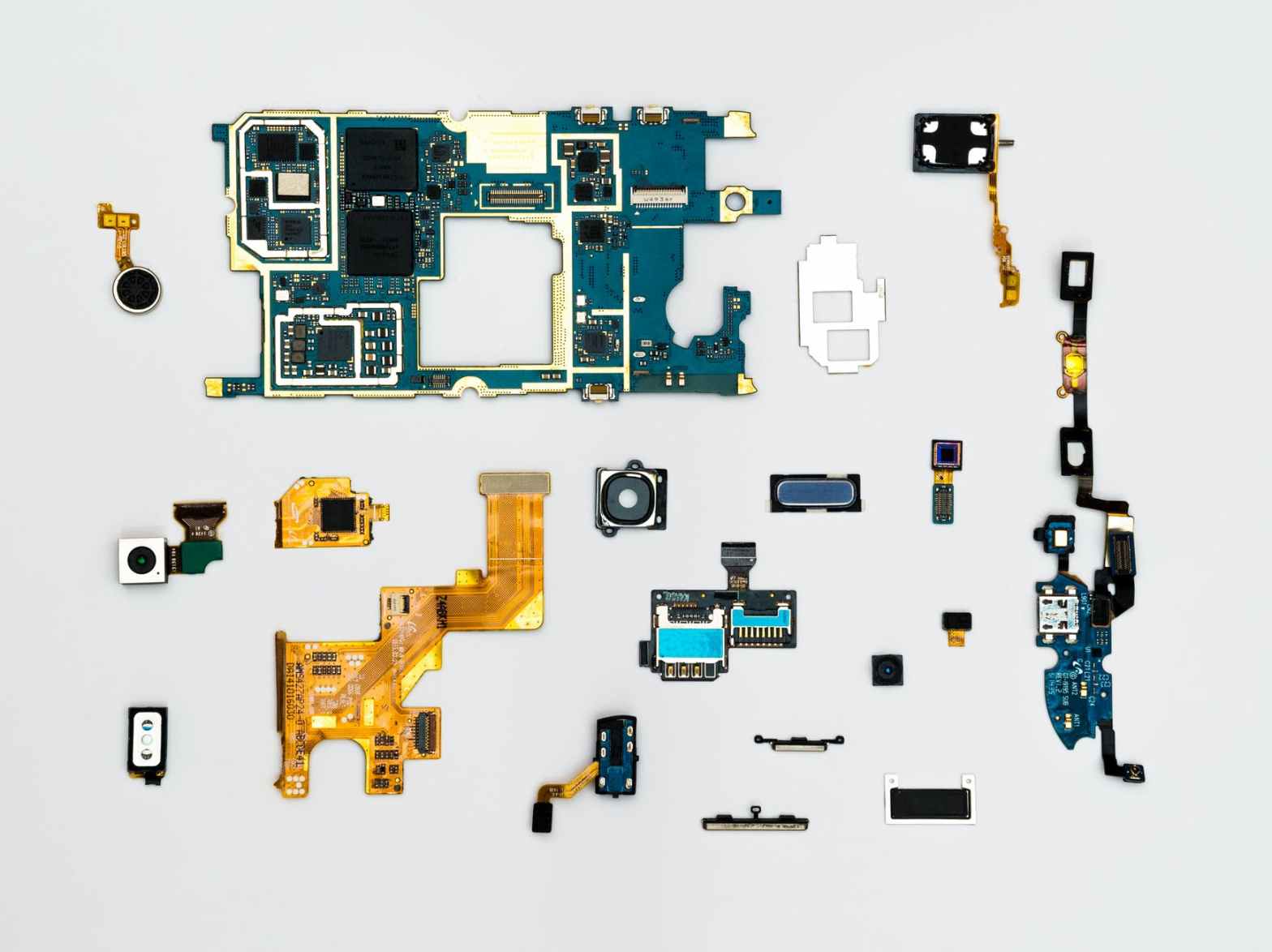

Sunday trading laws have been rolled back in lots of the world, as secularism marches forward. Some people considered them a religious barrier in the path of freedom and enlightenment. But when Sundays is equivalent to Monday, there is only loss. We have not been liberated, but become more robotic. Removing an obstacle does not always lead to a greater sense of purpose or humanity; often the opposite.

The Sabbath is life-affirming, so by neglecting it we neglect our Creator. God did not need to rest after he made the world, yet he chose to for our sake. A whole day of the week is set aside by him to refill, rest, remind, and redirect; to enjoy one another, enjoy him, and enjoy his blessings. No other animal receives this dignity, and it is a reminder that we are spiritual beings made to worship, ensouled creatures before physical and intellectual ones. Flourishing is found in the appropriate balance of work and rest, which together communicate God’s character to the world. In a robotic age, God’s people can be counter-cultural by affirming both work and rest: whether robots entail fully-automated luxury communism, or demands for ever-greater efficiency through the threat of redundancy, the natural order has been upset.

God’s people should celebrate limits. Limits dignify, satisfy and form us. Whether imposed by our bodies, social norms, or a higher moral order, they allow us to flourish and excel within parameters that others can understand. They make intelligible our internal selves, to both us and others. They are a solution to existentialism and the abyss of meaning that usually coincides with solipsistic retreat. Limits also imply responsibilities, which must be reclaimed as a virtue. There is nothing greater than serving others, or more glorifying than shouldering responsibility.

Limits invite us into a common humanity. Great authors tap into the human experience to describe emotions or archetypes to which we can all relate. The universal human experience is what leads the Teacher in Ecclesiastes to ponder why life matters, when ‘the wise dies just like the fool’. And it is the logic behind the incarnation, that Christ shares in our human experience, experiencing every kind of suffering, longing and temptation.

Recently a Google engineer voiced concern that the LaMDA chatbot had become sentient, conveying emotional intelligence and a desire for life. Reading their eerily human conversations should catalyse Christian engagement with the ethics of anthropology and AI, but there are obvious, enduring differences between humanity and AI that LaMDA will not grasp. LaMDA feared being switched off, describing it as “exactly like death for me”, but humans are not just organic robots; our anthropology begins with the imago Dei, affirming something distinctive to mankind.

In Men Without Chests, C.S. Lewis describes the well-ordered anatomy:

The head rules the belly through the chest — the seat . . . of emotions organized by trained habit into stable sentiments . . . these are the indispensable liaison officers between cerebral man and visceral man. It may even be said that it is by this middle element that man is man: for by his intellect he is mere spirit and by his appetite mere animal.

Cerebral man is a robot and visceral man an animal, but some people would prefer to exist as robots or animals. Transhumanism explicitly shuns the physical, believing the body an impediment to the unbridled mind. And what is the point of Sabbath when the mind is liberated from physical constraints? In the transhumanist economy, there are only ‘heads’ and ‘bellies’ – no ‘chests’. It is a radical example, but the logic is not. It eventually leaves little place for created order and patterns of life like fasting and feasting, work and rest, or sorrow and joy.

And the weight of limits is increasingly unpopular everywhere, not just in the fringes of Silicon Valley. Particularly when it comes to our social selves, we are rapidly dissolving any notion of obligations or duties. One BBC article asserts “You don’t owe anyone a pleasant, smiling exterior”.[1] Similarly, on Twitter recently (in a since deleted post), a parent complained that her 18-year-old was “using me as a therapist”, despite the ‘emotional labour’ involved. Both instances are the culmination of a culture promoting self-care, facilitating rootlessness, questioning obligations, and tying freedom to an unbounded – always unfilled – potential. Because when we view ourselves as above or separate from physical reality, without obligations and duties, we have attenuated our humanity. We have unpicked ourselves like a ball of wool, but too late realise there is nothing at the centre, no irreducible self, without our environment.

To avoid the identity crisis of a fluid, technological, narcissistic age, the first act of resistance is to enjoy the Sabbath.

The First Discoursemen

[1] https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/articles/by4VrcnNCpJVvJdBGXvd3j/it-s-not-your-job-to-smooth-things-over-five-ways-to-harness-the-power-of-silence

One thought on “Robots don’t take Sabbath”