The Professor finished his ale and looked over at the barman. There was no sign of him calling last orders, so the Professor sat back and toyed with his glass. Perhaps the barman was feeling generous with his time this Christmas Eve – or he didn’t want the coming day to come any quicker.

There was a clatter outside, what sounded like hooves on the cobbles. The barman walked slowly to the door and placed his hand on the latch. He braced himself with a sharp breath then pushed the door ajar. Someone must have spoken for he grunted and stepped out.

Heavy doors opened and shut and there was more of the clattering. The barman returned and without looking at the Professor strode past him to the fireplace. He poked around in it and flames shot up, licking their faces with warmth and shadows.

The door opened again and this time a cough came in, followed by a coarse cloud of white hair, a bent back and heavy fur-stuffed boots. All of this was wrapped up in cloth the colour of rust and somewhere inside was a man. He bustled over to the Professor and sat down on the other side of the fire with a mighty creak.

‘Father Christmas!’ the Professor cried. ‘It’s been some time.’

Father Christmas’ mouth crinkled and widened, his eyes swam with blue, and over his cheeks crept holly-berry red. ‘I got round a little quicker than usual tonight. And there’s not a much better place for a rest.’ He stretched out his feet to the flames, which themselves stretched out appreciatively.

‘It is certain now, you see. I am old. One is always getting older, and I am sure one continues to do so, but whatever I have been and whatever I will be, I am at this present time old.’

The Professor called for ale and smiled. ‘It is quite your own fault, you know.’

‘It is precisely my fault because it is precisely what I asked for. To open the window from eternity into time, just ever so slightly. And if I’m the man who comes through that window each year – well, it is quite worth it.’

‘He suffers who lives in time,’ said the Professor. ‘It is what the Master found, surely?’

‘Let us not make that comparison. His was very immortality and very mortality. It is only because of Him that the window is open at all, and for ever at that. That morning was something truly new. My small burden is to always age and never die, as you might say.’

He looked hard at the Professor, who replied, ‘But it is different for the children – you bring something new for them.’

Father Christmas sighed. ‘I try to open their eyes to it; let them see the stars in the dark sky. But it is getting harder. Mostly it is just a prayer here while they sleep, some words of blessing there.’

He felt in his pockets, then pulled out a wooden steam engine. It gleamed green with a tar-black cab. In golden writing on the side a plate read City of Truro. Rods and pistons glistened underneath as Father Christmas rolled the wheels on his thumb. ‘I still make these, but the children don’t wait to see the magic. They’re used to pressing a button and things happening straightaway.’ They gazed at the toy and the fire roared and smoked. Eventually Father Christmas put it back in his pocket.

‘Do you know that you could show a man eternity and he would find something to quibble about? They only see the window, and don’t look through.’

The Professor leant back. ‘Many must look through – we still feast and sing carols together. Surely these are glimpses of eternity. As long as a candle is lit in midwinter there must be hope?’

‘Yes, but only in that candle flame. I fear it dwindles, and the darkness grows around it. Look – ‘ The Professor looked around the pub. A few lone people sat drinking in silence. One man got up and and left the room on his phone; his beer glass stood empty on the table. Father Christmas called for ale and placed his hand on his own full glass. The Professor watched as the stranger’s empty glass filled from the bottom. It stopped half an inch from the brim; half an inch remained in Father Christmas’ glass, which he drank. The man on the phone returned. He looked at the nearly-full glass, then stamped off to find the barman. They heard his shouts about empty glasses and the cost of pints.

Father Christmas smiled sadly. ‘We dance and they sing a dirge.’

‘They do not imagine goodness and generosity anymore,’ said the Professor. ‘Wine and pudding and presents go some way. But we have forgotten that there is something underneath. To know love at Christmas, that gets us closer. A year comes though when love is no longer.’

‘The Master did it much better,’ confessed Father Christmas.

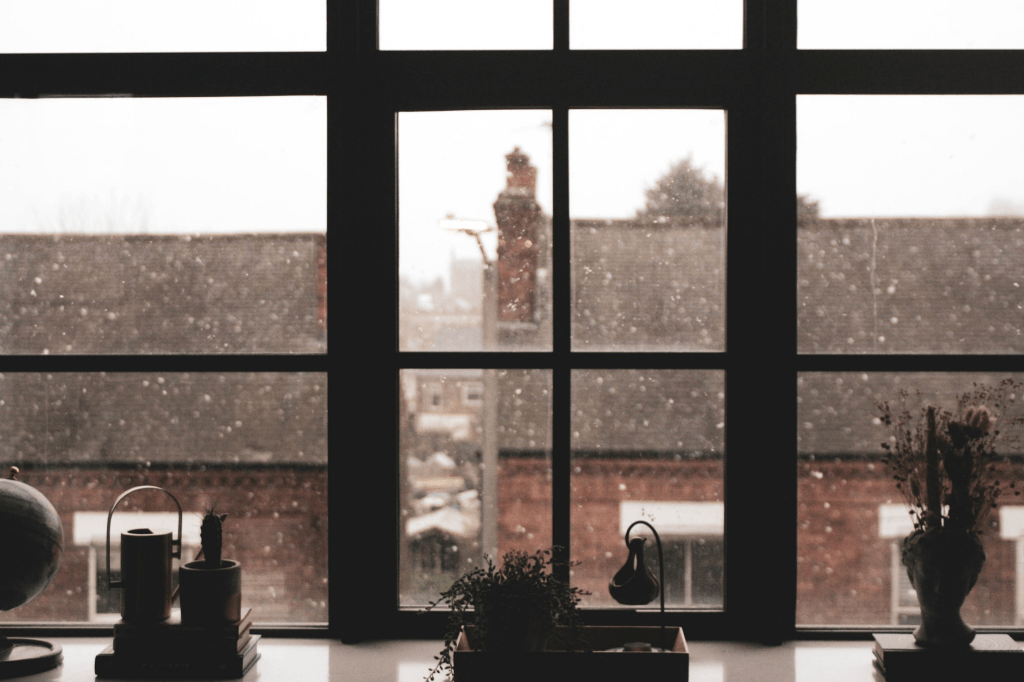

The room emptied gradually and the fire burned down. Frost gathered outside. At last a grey light crept in at the window. With it came the occasional sound of a car, and a dog barked. The Professor ran his finger round the rim of his glass. ‘Tell me. Why did you travel here tonight?’

Father Christmas’ white eyebrows raised slightly and he glanced at the window. He pursed his lips and had the look of a man remembering a tune. For a moment the wind stopped and the room was still. Suddenly a peal of bells burst through the air, flinging out their morning song, climbing up and up then tumbling over one another, rivers crashing down an icy mountain-side. Father Christmas was shaking with merriment, a fit of coughing seizing him, ale glasses rattling, the fire leaping again. The Professor looked out the window. A single star blinked out and the glory of the rising sun filled the sky. Drops of mist shone before his eyes. It had been a long time since he last heard laughter on Christmas morning.

The Second Discourseman